| Disc

1 1 Sonata in B Minor (Longo 263) 2 Sonata in E Major (Longo 23) 3 Sonata in C Major (Longo 104) 4 Variations Op. 34 Disc 2 Sonata Op. 20 No. 1 1 Allegro 2 Adagio 3 Allegro 4 Prelude Op. 45 5 Waltz in E Minor 6 Nocturne Op. 48 No. 1 7 Hungarian Rhapsody No. 12 8 Toccata in A Major 9 Intermezzo Op. 119 No. 3 |

Scarlatti Beethoven Kurka Chopin Liszt Paradies Brahms |

|

Fantasy in C Major Op. 15 5 Allegro 6 Adagio 7 Presto-Allegro 10 Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring (Chorale from Cantata No. 147) 11 Prelude and Fugue No. 9 12 Ballade Op. 23 in G Minor 13 Intermezzo Op. 118 No. 2 14 Ricercare and Toccata, on a theme from "The Old Maid and the Thief" |

Schubert Bach Chopin Brahms Menotti |

|

|

|

|

| WEBPAGES' BACKGROUND MUSIC | ||

| RPL WEBPAGE | SOUNDTRACK | CD |

| Home | Hungarian Rhapsody No. 12 by Franz Liszt | Disc 2, track 7 |

| CD | Ricercare and Toccata by Gian-Carlo Menotti | Disc 2, track 14 |

| Bio & Articles | Sonata Op. 20 No. 1, Movement 1 by Robert Kurka | Disc 2, track 1 |

| Photos | Intermezzo Op. 119 No. 3 by Johanes Brahms | Disc 2, track 9 |

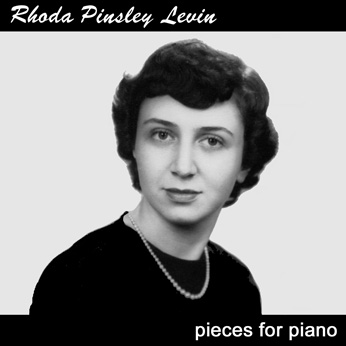

"Think of me when you play your Scarlatti," wrote

Miss Pinsley's fiancé Harvey J. Levin in 1954, on one of the

rare occasions when they were geographically apart. Scarlatti and

Beethoven were her home turf, even at a time when she'd suspended piano study and concertizing for a Masters in Music Education at Columbia and a more pragmatic

career as a teacher of choral music and piano. That enduring bond to

Scarlatti and Beethoven is evident in her 1963 recital's opener of three Sonatas by Scarlatti and Beethoven's Variations Op. 34. By that

time, she'd resumed piano study with Morton Estrin after a ten-year

hiatus. "She was reluctant to extol her virtues...[but] had nothing to be

modest about," remembers Estrin. "Her performance was clean and

intelligent...excellent qualities in her

interpretation."

Schubert's Fantasy in

C Major is "a real knuckle-buster," as Estrin describes it, one that Mrs.

Levin mastered "to great success." This powerful performance served as a

fitting closing for the first half of her program during her 1963 recital

tour. (It's no wonder her "knuckles" might have needed a

rest!)

Her return to performing had also been precipitated

by a dramatic change in her lifestyle. In 1959 she'd given up

schoolteaching for childrearing. In that environment, she felt compelled

to redirect her artistic energy, and now had the time to do

so. The sudden death of her mother months before her recital tour probably

gave her an additional need to move forward, musically or otherwise.

For her

first performance of a modern work, Mrs. Levin chose one by a friend, Robert

Kurka. Kurka had died of leukemia six years earlier at the age of

thirty-five. Mrs. Levin's husband Harvey had first met Kurka while both were

serving in the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (later reorganized as the CIA)

in Japan in 1946. They became close friends, and Mr. Levin introduced Kurka to his wife (music educator May Kurka)

while all three were earning their Masters in New York City. His most celebrated work was the opera The Good Soldier Schweik, completed during the

later stages of his illness and produced after his death.

My parents thought highly enough of him to middle-name me (their only child) after him. My mother's performance of his piano sonata even

influenced my own early composing.

In April 1963, her performance of Kurka's Sonata Op. 20 No. 1 was

received enthusiastically by an audience of over 200 concertgoers. The Westbury Times reported that "a highlight

of the concert was the presentation of flowers to her by the daughter of

composer Robert Kurka..."

She drew from her 1966 and 1963 programs for various performances over the next four years -- even while battling lupus, cancer and physical disability confining her to crutches, and enduring the deaths of her piano teacher and younger sister. She also continued raising me and served as vice president of the Hofstra-sponsored Pro Arte Symphony Orchestra League. Her last performance was in October 1970, four months before her death. Rather than hindering her, those life challenges seemed to give her music more meaning. Nor did she ever lose her sense of humor. Pianist Blanche Abram, who coached her during the last three years of her life, remembers "the combined strength of her intellectual and expressive abilities always evident" and "her delight at each new insight... It was an inspiration to me."

Bach's Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring, which opened Mrs. Levin's 1966 program, might seem an unlikely theme or message to be chosen by a Jewish solo musician. Yet, it was completely in character with Mrs. Levin to gravitate towards a piece despite any social or religious connotation. Like her husband, she was very much a citizen of the world, who also had me celebrate Christmas each year to bond with our Christian community and friends.

In addition to that program's regular repertoire of Bach, Chopin and Brahms, she embarked on another modern work,

Gian-Carlo Menotti's Ricercare and Toccata

, on a

theme from The Old Maid and the Thief. Menotti had long been a favorite

composer of hers. In the early 1950s, not long after its world premiere on

television, she had selected, directed and performed piano on Menotti's

Christmas opera Amahl and The Night

Visitors for a public school production -- a challenging project for

youngsters that received extensive coverage and praise in the local press.

I was raised on her record album of that opera. She also took me to a New

York City performance of Menotti's 1968 opera The Globolinks. Given her unusual

affinity for Menotti despite a general discomfort with modern music, it seems

apropos that she chose one of his pieces and closed out her career as a pianist

with it (just as it closes this CD collection.) "She told me three years

ago she was living on borrowed time," said Edward N. Beck, manager of the

Pro Arte Symphony Orchestra, shortly after her death in

February 1971. "But she just went on about her business and there was no

complaining from her about it."

Mrs. Levin was honored by Oberlin Conservatory of

Music, Harvard University, and Hofstra University, which includes the

Rhoda

Pinsley Levin Endowed Award for Excellence in Musical Performance. Her

achievements were featured in numerous newspaper articles and touted by

composers Gabriel Fontrier and Elie Siegmeister. Still, as a

pianist, she was a paradox. She was exceptionally talented, highly

trained, technically proficient and musically sensitive.

Her playing didn't merely impress listeners but deeply moved them as

well. Yet, her humility prevented her from ever being

content in the role of solo concert pianist. Her piano work had begun with lessons at the age of four, and seen her through

New York City's High School of Music and Art, Oberlin Conservatory of Music, the

national music honor society Pi Kappa Lambda, national touring and radio work as

pianist in the Oberlin Woodwind Ensemble, and as accompanist in a slew of other

capacities over the years. But she didn't live long enough to

further develop her concertizing. "The good really died young in her case," says

Morton Estrin.

More than by public honors or published praise,

her musicianship is best summed up by several of her mentors and

colleagues. Beryl A. Ladd, one of her piano professors at Oberlin,

characterized her playing as having "not only...all the traditional skills of

speed, articulation, clarity, but...a wonderful sensitivity to tone and

phrase...[that] turns notes into something that lives and breathes...

[The] music is alive... There is no getting away from this cleanness and

clarity -- this freshness -- it is like standing on the top of a

mountain." Mrs. Levin's colleague Carol Block Whited described her

performance as having "a clarity and depth like that of fine wine... Her

soul shined through her fingertips, and there was a lot of beauty in everything

she played, whether it was solo music, accompaniment, or chamber music."

Pianist Audrey Schneider considered Mrs. Levin "one of those rare musicians who

performed at the highest professional level without ever losing sight of the

fact that the music was more important than she or her ego was. She always

listened with extraordinary care, whether the performer was a student, a

colleague, a concert artist...or herself. Her essential modesty and

unwavering standards never allowed her to be overconfident or complacent.

She sought and achieved ever-increasing mastery, not for her own glory, but

because that was what the music deserved!"